For most U.S. businesses, the pandemic forced temporary (and sometimes permanent) closures, bankruptcies, and credit crunches. Many were forced to adapt to working remotely, deal with border closures and shortages, or address outbreaks. But for at least one kind of entity, 2020 was a banner year. Patent Assertion Entities (PAEs), entities that exist to acquire and enforce patent assets, filed upwards of 3,744 suits, up more than 12% over 2019—the vast majority of patent cases filed. For patent lawyers, at least, business has been booming.

One particularly prolific NPE filed almost 200 suits since March 2020, representing 1 out of every 20 district court cases nationwide: WSOU Investments LLC, d/b/a Brazos Licensing (i.e., “we-sue”). WSOU is a new kind of patent troll in terms of scale—but it’s one built on an old file-and-settle model and run by the now-infamous Craig Etchegoyen (the guy behind the litigious NPE Uniloc), he’s gone from 600 patents being asserted through Uniloc to a web of over 15,000 Nokia and Alcatel-Lucent patents and applications from over 4,500 patent families. Most of the patents in the portfolio (and most of the patents asserted) relate to telecommunications and digital data processing and transmission, although they cover a range of fields, including wireless networks, video games, and image processing and communication. Over 5,000 of these patents are US Patents:

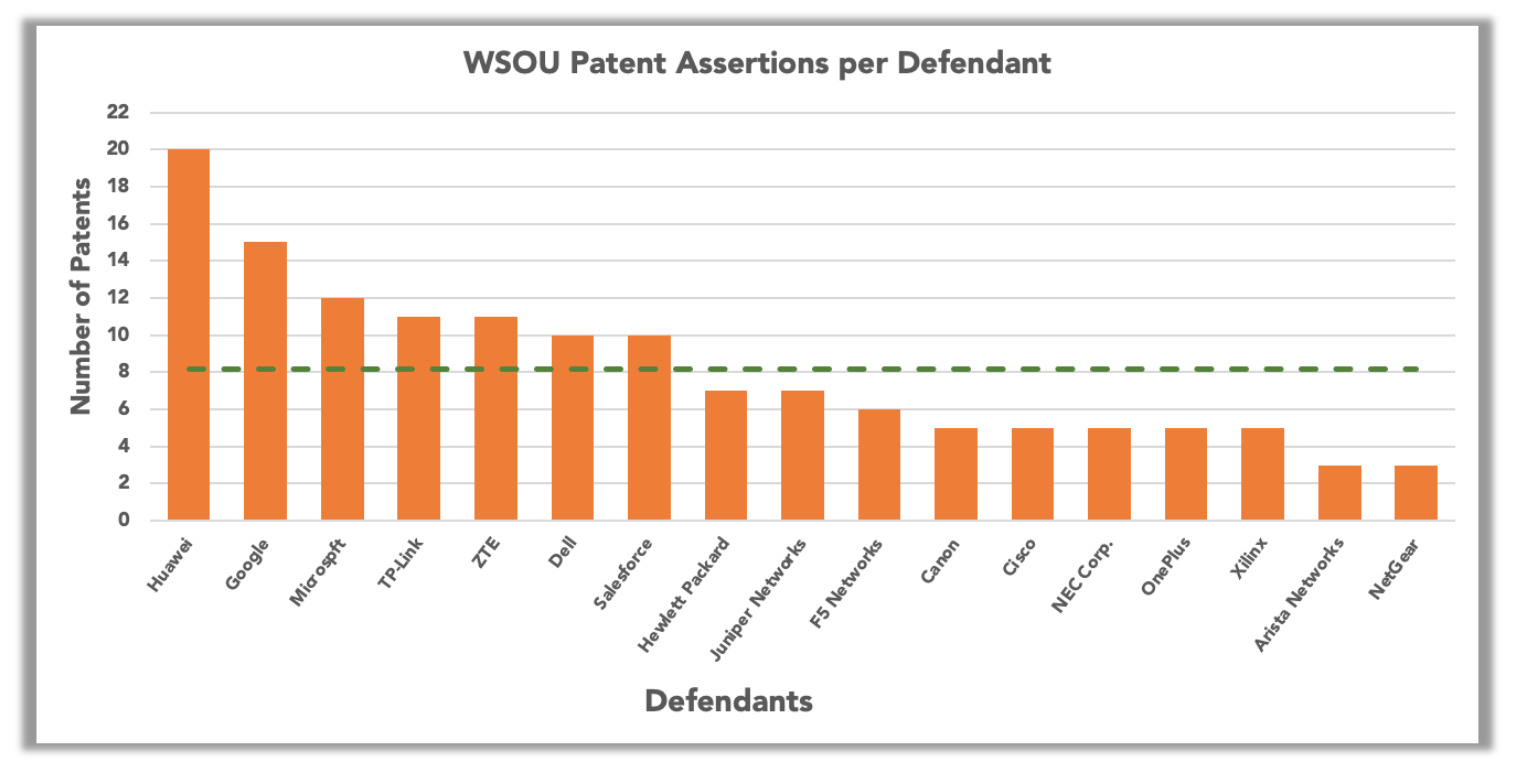

WSOU takes a “darken-the-skies” approach to litigation that forces operating companies to either settle or fight, on average, eight lawsuits at once. One defendant, Huawei, has the unrelished honor of finding itself defending against 20 of these patents in dozens of suits, with Google close behind at 15.

Rather than assert a few related patents against similar accused products or make any attempt to consolidate or streamline matters for the courts, WSOU instead clogs them, running up court costs and concerns with multiple single-patent cases against a wide variety of different accused products, relying on patents from different families for each defendant. Indeed, when accounting for transfers, 98% of the patents asserted come from unique families.

WSOU appears to be picking defendants off in a way that prevents any sort of joint defense, common interest, or other means of defending themselves, and then seeking to license the whole shebang seriatim, keeping all discussions separate and isolated. To wit, WSOU has not asserted the same patent twice against different defendants.

It isn’t hard to see WSOU’s play here. By filing individual suits involving different patents, WSOU makes it expensive to perform prior art searches and develop non-infringement and invalidity contentions for each case. Accounting for refilings and transfers (which are often involuntary), WSOU has filed over 90% of its cases in the Western District of Texas, a known hotbed for PAEs ever since a particular Waco judge has created a reputation of hoarding patent cases with promises of fast resolution, even despite repeated admonitions from the Federal Circuit.

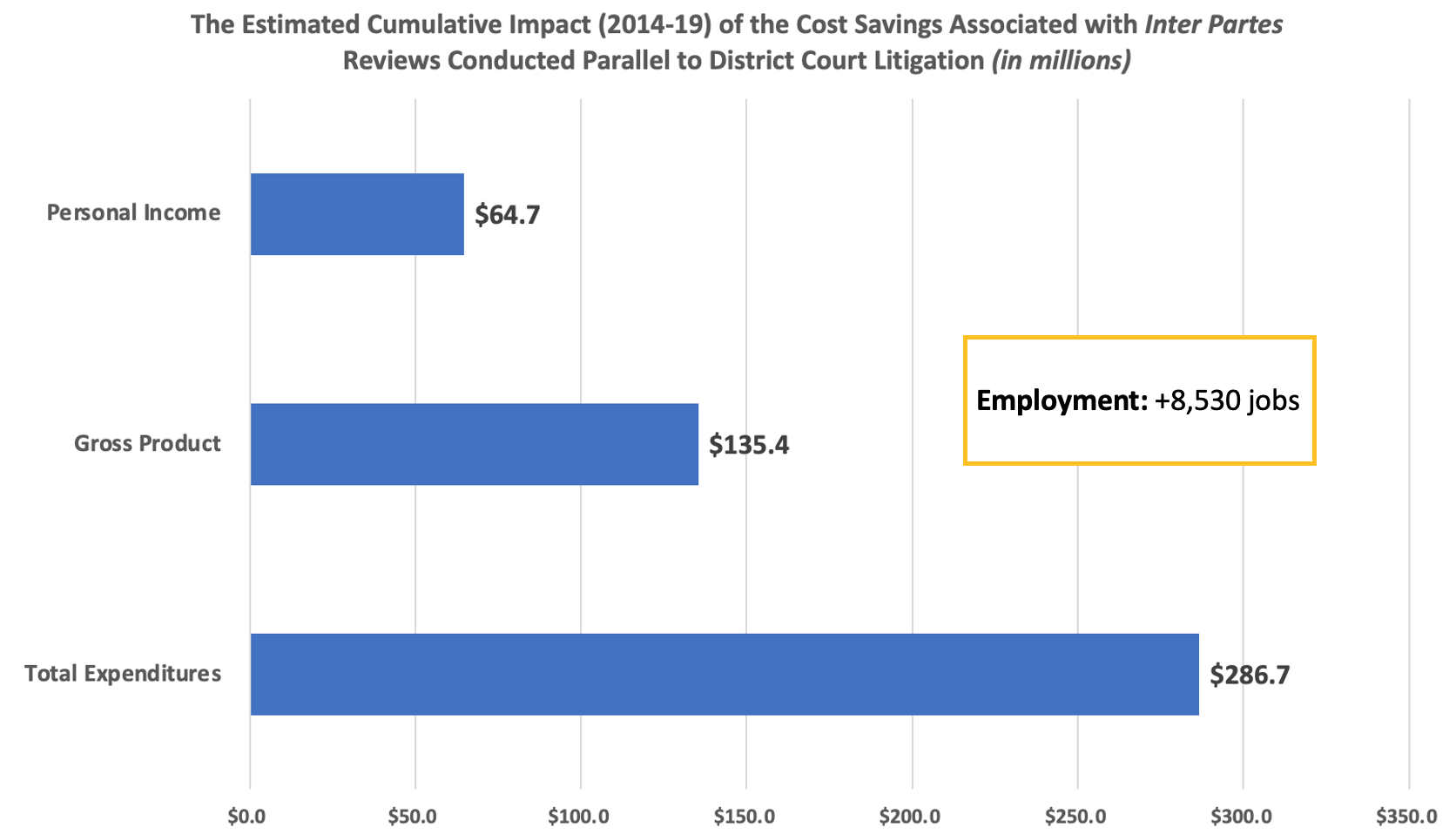

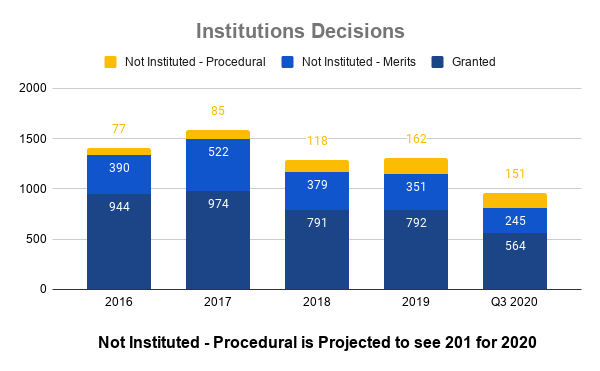

By litigating in well-known “rocket dockets” where it can, WSOU makes it difficult for defendants to meet the statutory requirements for filing IPRs, and filing all of those IPRs would not only be expensive (the filing fees alone, not including the cost of attorneys and experts, would cost about $250,000 for the average campaign per defendant, assuming one IPR per patent), but also somewhat superfluous when the presiding judge over almost all of the cases has a avowed policy of refusing to stay a case unless the defendant somehow manages to petition for inter partes review before they are even sued.

While the effectiveness of this boil-the-ocean approach is questionable, it certainly was foreseeable. With a one-year statutory bar to file any kind of expensive defensive challenge (a year being pretty generous under Apple v. Fintiv), and no obligation for patent owners to forewarn defendants about their patent portfolios, a patent owner would almost be foolish not to quietly build up a line of cases to spring on defendants all at once, and use the filing as a sort of ransoming starting point for negotiations once companies are staring down the barrel of millions of dollars in court costs. When the cost of defense can be upwards of $4,000,000 over three years, while it’s still hard to comprehend, defendants can at least budget ahead for the defense. When the cost is multiplied by a dozen and sprung upon you on questionable patents, it can be a little harder to justify defending oneself.

Theoretically, this strategy should also be relatively expensive for a plaintiff. But WSOU has this down to a science. Using a firm that does work almost exclusively for Uniloc and WSOU, his hope is that the high costs of defense force defendants to surrender to settlement early. This is particularly true given WSOU’s relationship with RPX. For an additional subscription, RPX (it appears) offers settlements for WSOU’s entire portfolio, creating a cycle of monetization that is antithetical to patent assertion deterrence.

WSOU is managed by Craig Etchegoyen, surfing-prodigy-turned-PAE-manager. Etchegoyen is the former CEO of Uniloc, another prolific PAE. In December 2020, it was discovered that based on a contract clause that gave a litigation financier a right to take ownership of patents if certain revenue targets were not met, Uniloc did not have standing to assert its patents. WSOU may be subject to similar contract clauses, and discovery into ownership and chain of title is already in process. A defendant would be wise to pore through assignment and financing agreements to catch any chink in the chain of ownership—the assignment frames on record with the USPTO do not, for instance, show a clear chain of title for many of the WSOU patents. Rumor has it that he tried and failed to find a buyer for the portfolio, bringing unreasonable demands to the table. It’s likely that his current demands are equally unreasonable, but he’s leveraging the cost of litigation as far as it can be leveraged in an attempt to avoid any sort of honest look at the value of his portfolio.

It is too early to tell if WSOU’s strategy will pan out, but most defendants have not yet taken advantage of the inter partes review process, presumably because the costs there would extend into the millions just to file, and with the substantial uncertainty surrounding Fintiv and other USPTO flexes of discretion, it’s unclear if even meritorious challenges will be given the time of day. Of the 140+ patents asserted, so far just 12 PTAB challenges have been filed, including one IPR by Unified Patents against a video codec patent. Unified has also posted a number of PATROLL contests (US8209411, US7409715) and continues to monitor WSOU’s monetization activities.