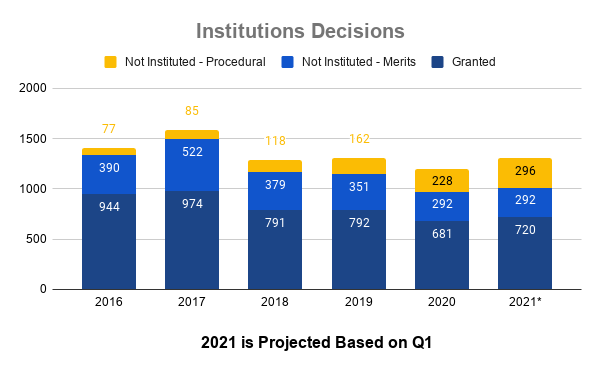

It has been a banner quarter for those trying to avoid merits-based review of their patents at the USPTO. With 74 procedural denials to start the first three months of 2021—a quarterly record—it is projected that denials will rise by nearly 30% for the year, from 228 to nearly 300. If this trend holds, the Board will deny more petitions in 2020 without reaching the merits than in doing so. That’s in just over a year of Fintiv itself being precedential. If that projection holds, that will mean more than six hundred petitions will have been paid for and filed with the Board that will not have gotten a hearing on the merits.

It appears that the PTAB will use the same number of 314(a) denials as last year. Interestingly, the total use of either 314(a) denials or 325(d) denials appears to be slated for a 3.5% increase over last year.

It is worth noting that so far, those benefiting from the rule tend to be litigation-financed entities filing in district courts with aggressive ersatz trial schedules, with the vast majority being related to cases filed in the Western and Eastern District of Texas. Assertion vehicles like VLSI and Uniloc (Fortress IP and Softbank), Solas OLED and Neodron (Magnetar), AGIS Software Development, LLC, Monarch Networking Solutions (Acacia). Clear Imaging Research, LLC (Soryn IP Group), Michigan Motor Technologies (Equitable IP), Personalized Media Communications, PanOptis (Brevet Capital), and Huawei (against a U.S. company, Verizon) have all benefited from avoiding having the Office consider the merits of their claims—in some cases resulting in huge money judgments on challenged but never-reviewed claims. It has also been regularly used by the likes of fracking companies, foreign cigarette companies, and other overseas parties, for example, largely against U.S. practicing companies. Indeed, some those same companies went on to win big money judgments, totaling a record $4.7 billion awarded in 2020 through trials despite the pandemic (and this was pre-$2.18 billion in the VLSI case).

In other words, the biggest beneficiaries of the Fintiv rule—by a longshot—are well-funded non-practicing entities, in particular, those run by the litigation financier Fortress IP—itself touting those victories on the way to fundraising for another $900 million dollar fund for future assertions. See Richard Lloyd, Fortress’s Latest Patent Fund Could Top $900 Million, IAM Media (Apr. 9, 2021), available at https://www.iam-media.com/finance/fortresss-latest-patent-fund-could-top-900-million (reviewing pitch materials touting a “gross, unlevered internal rate of return of at least 20%”). All this in the just-over-a-year of the Fintiv rule’s precedential life (it was designated precedential by the Office just March 20, 2020).

This trend can be seen below, by combining 314(a) and 325(d) denials together versus all other procedural denials.

Looking at the last six years, 314(a) denials are now used by the Board 12.1% of the time, an increase over last year.

Meanwhile, 325(d) denials continue to fall in line with the previous years, and were used only around 5% of the time.

It would appear that the NHK Spring/Fintiv framework is picking up right where it left off in 2020, and accelerating. With 43 denials using this framework in the first quarter of 2021, this is projected to nearly double to 172 from last year’s 85.

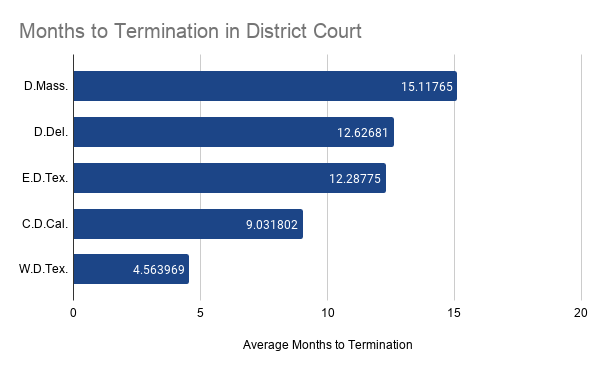

Interestingly, there has been explosive growth in denying a petition using the NHK Spring/Fintiv framework when the patent in question is being disputed in the Eastern District of Texas, Western District of Texas, District of Delaware, District of Massachusetts, or the Central District of California. While most numbers are expected to remain the same from last year, the Eastern District of Texas is expected to see the denials double under this framework.

Of substantive note is the trend of denial decisions ignoring increasingly overwhelming evidence that the trial dates parties base their Fintiv arguments on are entirely illusory or, at best, highly aspirational—both case-specific and court-generalized data tends to be ignored for whatever is listed in a court’s standing order. The Western District of Texas, for instance, has never even come close to meeting the trial dates listed in their standing order; the Eastern District of Texas (particularly this and last year, after outbreaks and closures related to COVID) is laboring under a growing backlog and does not appear to be set to meet or exceed trial date expectations any time soon.

In one recent example, Nine Energy Service Inc. v. NCS Multistage Inc., IPR2020-01615, the Board declined to take up the merits based on a standing order-scheduled October trial date in the Western District of Texas (in March), despite both general evidence that that Court has never hit their aggressive target scheduled trial date before (and in 2020 increased their time-to-trial delay by 5 months on average) and specific evidence that the case would almost certainly be consolidated and moved back to accord with later-filed actions among the same parties. The patent, a relatively recently issued patent on fracking technologies, U.S. 10,465,445, had not been challenged previously.

When looking at 2019 through the first quarter of 2021, two Texas jurisdictions predictably lead the charge when NHK Spring/Fintiv framework is used in a denial. Here (largely based on the number of mature cases on that court’s docket, and despite numerous stoppages of all trials over the same time period), the Eastern District of Texas leads denials at 38.3% of the time, followed by the Western District of Texas at 23.9% of the time (though that number is set to rise after that court’s docket exploded in 2020). See also Lex Machina Patent Litigation Report 2020 (March 2021) (noting yearly patent suits increased for the first time since 2020, driven by Western District’s 857 patent cases in 2020, with Judge Albright receiving 793 complaints, comprising 19.5% of all patent cases nationwide).

When looking at the average months to termination in 2020 based on settlements, three of the venues are averaging just over a year, up from previous years. Multiple sources and data reports show that time-to-trial in the Western District, for instance, is up five months on average from an already-behind average that does not comport with that district’s trial date standing order schedule. See, e.g., Lex Machina Patent Litigation Report 2020 (March 2021) (noting that median time to trial in patent cases nationwide was 135 days longer in 2020 than 2019).

This begs the question on just how effective is the NHK Spring/Fintiv framework in the first place for assessing potential conflict between fora, if (as the evidence demonstrates), district court litigation is taking far longer than hoped for in nearly every case, even while most of the denials occuring in the PTAB are based primarily on those projections. Indeed, in both NHK Spring AND Fintiv themselves (as well as other high-profile denials under Fintiv, like the VLSI (Fortress IP) denials), the trial dates were all pushed back substantially, in all cases past what would have been the projected final written decision date—indeed, in Fintiv itself, the Board would have issued a final written decision had it instituted on the merits by last month, March 20, 2021. Compare, e.g., Apple Inc. v. Fintiv, Inc., IPR2020-00019, Paper 11 (PTAB Mar. 20, 2020) (denial based on November 16, 2020 trial date) with Fintiv, Inc. v. Apple Inc., No. 1:19-cv-01238 (W.D. Tex, filed Dec. 21, 2018) (still pending trial). Whether a reassessment of the wisdom of the practice will ensue remains to be seen, but evidence is mounting that scheduling order trial dates are of little reliable or probative value in assessing objective indicia of even perceived conflict.

Copyright © 2021, Unified Patents, LLC. All rights reserved.